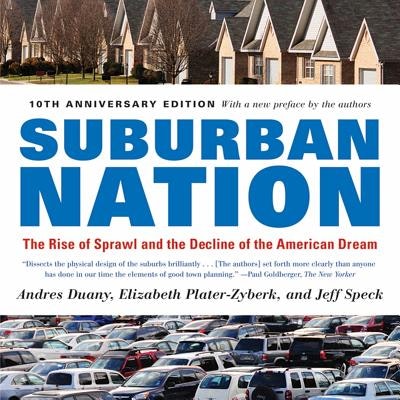

Key Takeaways and Book Review of Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream

By Anar Salayev, San Diego & Bay Area Correspondent at Pedestrian Space

Takeaways

Main argument:

Unhinged suburban growth (read: sprawl) has drained vitality from downtowns, segregated communities, bankrupt cities, and led to a society that is dependent on the personal automobile.

Consequences of suburbanization

The built environment has a very real effect on human behavior – the suburbanization has pushed us to further alienate ourselves. We live far away in distant exurbs, wherein we focus more on the inside of our home than the commons without, wherein we get in our car in the morning to get to work from which we drive back at night, wherein we go in our homes to sleep, rinse, and repeat. As we continue to experience the world through the windshield, we become far-removed from, abstracting them to pedestrians, cyclists, and other cars.

“Life once spent enjoying the richness of community has increasingly become life spent alone behind the wheel.”

Suburbia makes life difficult for many groups that cannot drive – children, teenagers, victims of disability, the elderly, the poor. These individuals are then made dependent on parents, caregivers, and expensive chauffeurs, or relegated to a public transit system that was put in more as an afterthought (or subsidy) than a genuine investment.

Suburbia also makes life difficult for the groups that can own a car. The sprawl of cities, hierarchy of roads, and the endless cycle of car dependence guarantees congestion, long commute hours, expensive road maintenance costs, physical and mental health ramifications, and ecological destruction.

What can be done?

Growth cannot be stopped – it can only be guided and mitigated. Most societal issues that stem from growth are interrelated – traffic, housing, crime, health, the environment. They must be tackled together.

The authors also make it clear that suburbs can be good – the cities that annexed their suburbs are generally financially successful and aren’t undermined by suburban competition. However, they should not be constructed at the expense of the urban core and surrounding environment. Thus, suburban development should be done deliberately, with equal amounts of funding and incentives going towards urban infill and exurban/rural conservation.

Proper development of a community requires multiple actors to work in tandem.

“To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts”

– Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854)

At the top, it is the role of government, across all levels, to ensure that neighborhoods and cities are designed properly. The current situation we are in is a direct result of top-down policy – in order to address it, cities (and more importantly, regions) must drive their own destinies. By working as a region, policymakers can ensure that adjacent cities are not competing with one another, but rather cooperating in the development of more sustainable land-use patterns.

The authors stress the partnership of architecture and urban design – present day architects should further insert themselves into discussions of urban design and planning (as opposed to act as mere consultants). Without a synergistic approach, urban design is left at the hands of transportation engineers, whereby architects claw for relevance by making their practice more and more abstract and idealistic.

Finally, citizens must advocate for themselves and their neighborhood – civic duty is necessary to ensure a fairer, more equitable community for all. This civic duty should be supported and encouraged by equitable housing, land use, and transportation policies. Citizens cannot be expected to be involved in community planning without first ensuring their own security and well-being.

Book review

Suburban Nation took me a while to read – it is so densely packed with information. The authors are clearly passionate and authoritative about urban design. Their main argument is that the United States post-war boom and subsequent zoning laws resulted in a nation that is defined by suburbia and automobile dependence. “Life once spent enjoying the richness of community has increasingly become life spent alone behind the wheel.“

This suburbanization has drained inner cities, (further) segregated communities, bankrupt cities, and led to an entire society that is dependent on the personal automobile. The nuances and consequences of suburban development are compared to those of traditional neighborhoods (i.e., those neighborhoods that were “organically” built prior to the proliferation of the automobile). I appreciate that they appeal to both economics and human psychology to bolster their argument. For example, when presenting case studies of neo-traditional development (specifically, neighborhoods that they’ve helped design), they frequently compare the growth in property values to neighboring modernist neighborhoods. They attribute this difference in value to desirability, desirability that stems from people’s intrinsic need for community. The entirety of chapter 7 (aptly titled “The Victims of Sprawl”) illustrates the psychological consequences of modernist development while continually tying them back to ways they can be addressed with more traditional neighborhood design.

One thing some readers might not appreciate is how prescriptive some of the authors suggestions are. They liberally use the words “must” and “should” in instances that may require a bit more elaboration. However, when reading the book in its entirety, one understands that the authors are not declaring some “war on suburbia” but are rather proposing options. They’re not arguing that everyone should give up on their 3,000 square foot McMansion in the exurban fringe; rather that governments should allow for (and in fact, incentivize) the development of other types of homes and neighborhoods, homes and neighborhoods that encourage active transportation (walking, biking), community, and ecological sustainability.

While I recommend this book to anyone interested in urban design, I suggest reading Curbing Traffic by Chris and Melissa Bruntlett first – it’s a bit shorter (240 vs. 358 pages) and published more recently (2021 vs. 2000).

Rating: highest possible score 4

Writing style 3

Entertainment value 2.5

Layout; Structure; Delivery 4

Information: 4

X-factor 3

Overall rating 3.3

Anar is a car-enthusiast turned walkability advocate. He seeks a holistic understanding of the built environment. He believes that human-centric urban design will go a long way in combatting climate change, encouraging sustainable practices, and improving health outcomes – both mental and physical.

Read San Diego and Bay Area Correspondent Anar’s content here

Learn more about the Global Walkability Correspondents Network here