Yes Exit: A Successful Activist Campaign

By Dylan Reid

Walking activism in Toronto is generally a slow and halting process. It is hard to get the attention of politicians and City staff, and often difficult to make visible and rapid progress on issues.

But, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the organization I am part of, Walk Toronto, succeeded in getting a pedestrian change implemented rapidly. It was a modest change, but it addressed a long-standing source of irritation to pedestrians and opened up the city to more walking. It’s an interesting case study in successful pedestrian advocacy.

“The pandemic has led many more people to walk in their neighbourhoods, and as they get to know their community, they have become more acutely aware of this kind of misleading signage. At the same time, the City of Toronto has realized the value of walking for health, mobility, and the environment. That commitment requires that the City’s signs consider the needs of walkers as equal to the needs of drivers.”

Walk Toronto is a grassroots, all-volunteer group. We do not have a budget or staff, and operate through a steering committee and a mailing list of supporters. We seek to push for improvements that make Toronto a better city for walking, to represent the pedestrian point of view to politicians, City staff, and the media, and to raise awareness of pedestrian issues through events and social media.

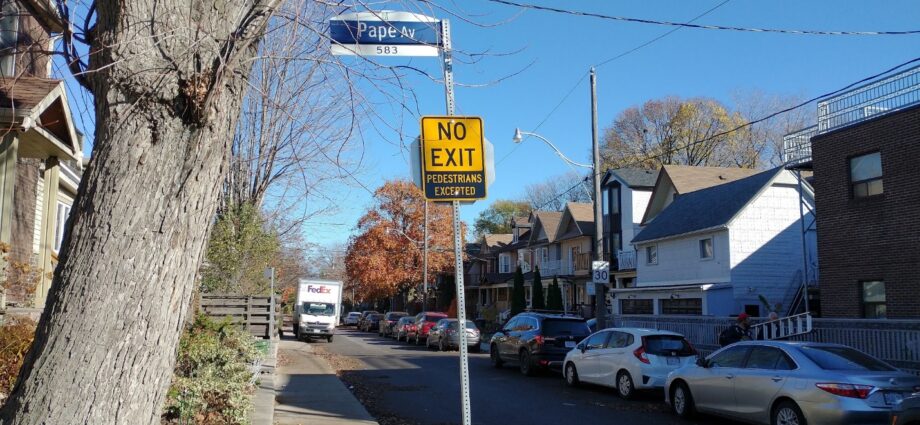

Until recently, dead-end streets – streets that did not have an exit for motor vehicles – were marked in Toronto by yellow signs with the words “No Exit” in bold black letters. In many cases, these were streets where, in fact, someone on foot could exit. They might be streets that were closed to vehicles for traffic calming but where the sidewalk continued, or that ended in a park with a path, or a slope with stairs. But people walking by who might have been tempted to explore the street would have no idea that they could in fact go through.

These signs, in other words, embodied the City government’s vehicle-centric attitude to Toronto’s streets, where the primary purpose of the streets was to move drivers efficiently and other ways of getting around were considered secondary and of little importance.

These signs had been an irritant to pedestrians for a long time, but no-one had been able to get any action on them. However, when the Covid-19 lockdown happened and people began to go for walks around their neighbourhood for their physical and mental health, they became much more aware of their neighbouring streets and of the incongruity of these signs.

Inspired by comments to this effect on social media, Walk Toronto embarked on a campaign in January 2021 to change these signs, where appropriate, to accurately reflect when they did not apply to pedestrians.

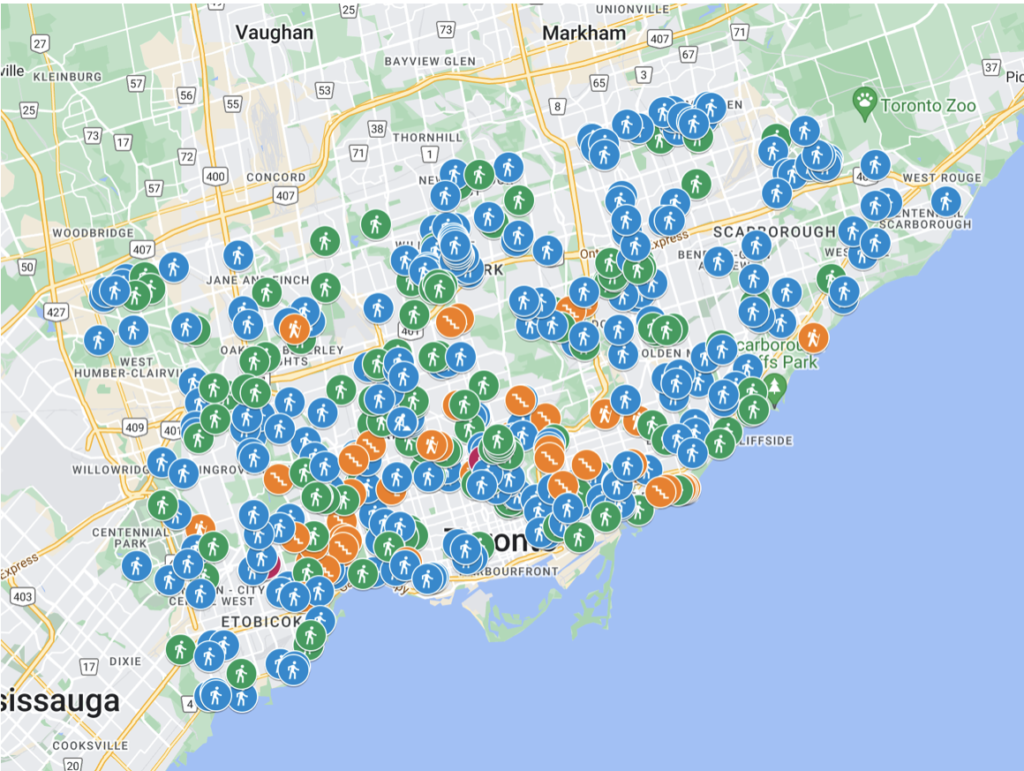

The first phase of the campaign was to create a crowd-sourced map of instances in Toronto where this situation existed. Walk Toronto’s Sean Marshall, a trained geographer and map-maker, took on this task, using Google Maps. To source examples, Walk Toronto used social media (Twitter, Facebook) and its newsletter mailing list, in addition to Sean’s own research using Google Street View.

There is a tendency for politicians who represent the suburban parts of Toronto to dismiss walking concerns as limited to the older and more walkable parts of the city, but the map showed that it was an issue in their constituencies as well.

The map rapidly grew to over 450 instances. The map accomplished several things. First, it showed that the problem was frequent and thus worthy of attention and action. Second, it showed that the problem was present in all parts of the city, not just the more walkable older parts of the city. There is a tendency for politicians who represent the suburban parts of Toronto to dismiss walking concerns as limited to the older and more walkable parts of the city, but the map showed that it was an issue in their constituencies as well. Third, it created a strong visual embodiment of the problem that grabbed people’s attention. Finally, it gave the city an existing road map for implementation, meaning that it would not take up a lot of staff time.

Another key part of the campaign’s success was a clear and easy-to-implement objective. We sought an addition to the signs, where appropriate, that said “Pedestrians excepted.” This idea built on existing street signs in the city that said “Cyclists excepted,” for example on one-way streets that have a cycling counterflow lane. If this extra wording could be added to those street signs, it seemed entirely possible to do the same for No Exit signs.

The campaign and map generated media attention, and Walk Toronto representatives were willing to appear on TV, on the radio, and in print to argue for this change. This willingness helped generate momentum, public support, and additional contributions to the map.

The next step was to get political support. By including a city councillor known to be supportive of pedestrian initiatives, Paula Fletcher, in a Tweet about the campaign, we were able to get her interested, followed up by emails to get her fully on board. Direct discussions developed a simple strategy for putting the proposal to the city council. Walk Toronto submitted a letter to Toronto City Council to show support for the proposal. We wrote, in part:

The campaign and map generated media attention, and Walk Toronto representatives were willing to appear on TV, on the radio, and in print to argue for this change. This willingness helped generate momentum, public support, and additional contributions to the map.

“The pandemic has led many more people to walk in their neighbourhoods, and as they get to know their community, they have become more acutely aware of this kind of misleading signage. At the same time, the City of Toronto has realized the value of walking for health, mobility, and the environment. That commitment requires that the City’s signs consider the needs of walkers as equal to the needs of drivers.”

Thanks to the clarity and affordability of the proposal, the motion passed easily, and staff was directed to implement it.

Walk Toronto worked a little with staff to refine the proposal. Notably, we have long been concerned with accessibility, so we persuaded staff to indicate when a pedestrian exit was not accessible to those in wheelchairs.

City of Toronto staff have not always been known to implement directives with alacrity, but in this instance they did. We cannot say why, exactly, but the simplicity of the solution and the fact that we had already crowd-sourced the locations may have helped. It’s notable that suitable locations that did not appear on the map did not get the signs in the initial roll-out, although in some cases residents have been able to get them added later.

By summer, several hundred new “No Exit – Pedestrians Excepted” signs had been rolled out across the city.

In less than half a year, we succeeded in fixing a long-standing irritant for Toronto pedestrians, making walking more visible, and encouraging people to explore the hidden corners of their neighbourhood on foot rather than discouraging them. As Sean Marshall wrote, “Knowing where one can walk, especially away from heavy traffic or busy sidewalks and paths, will only help unlock the city for more Torontonians.” It was a rare but very satisfying example of a rapidly successful walking activism campaign.

Dylan Reid is the executive editor of Spacing magazine, a quarterly print magazine and online news feed covering Toronto’s urban landscape. He has written extensively about pedestrian issues in the magazine, and also for other publications. He is also a co-founder of the volunteer advocacy group Walk Toronto, and is a former co-chair of the Toronto Pedestrian Committee, which was an official advisory body to the City of Toronto.

Read Toronto Correspondent Dylan’s content here

Learn more about the Global Walkability Correspondents Network here